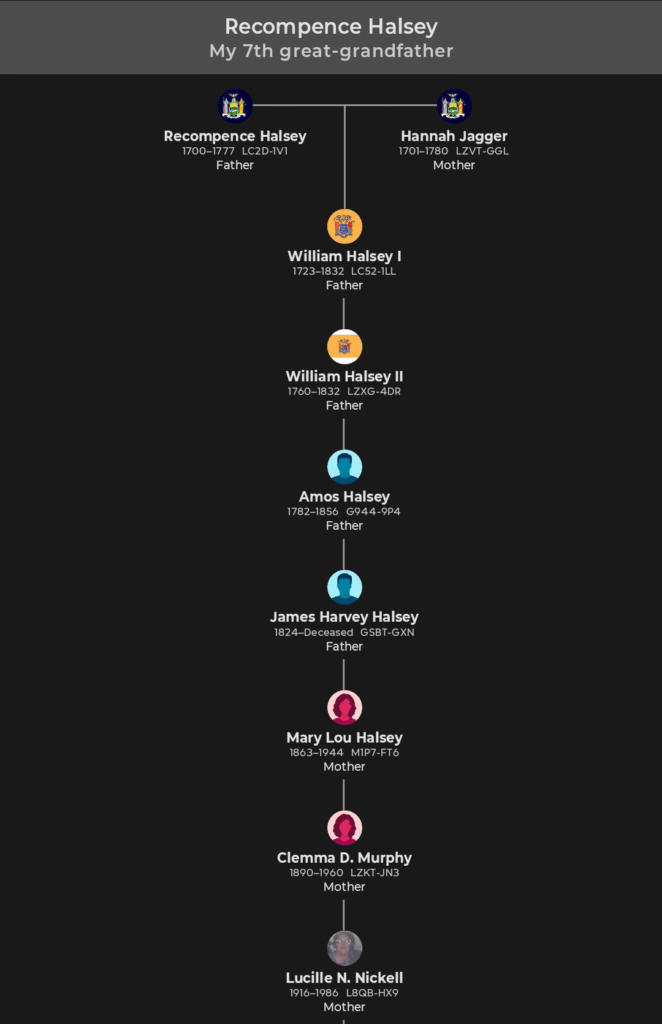

Recompence Halsey 1700 to 1777: Long Island to New Jersey (and Hannah [Anna] Jagger)

I first met Recompence Halsey on a quiet evening of family sleuthing at AboutMyFamilyTree.com. There he was, my seventh great grandfather, born August 19, 1700, in Southampton, Long Island, New York Colony. He married Hannah Jagger, raised a very large family, then headed west into New Jersey. He died on May 3, 1777, in Afton, Morris County, just as the Revolution was reshaping everything.

Picture his world. Southampton was an English town by the sea, built on farming, fishing, and small trade. Sundays meant church, weekdays meant fields and fences, and town life ran on kin networks and land boundaries. News moved by horseback, not headlines; loyalty to crown and community sat side by side, at least for a while.

Recompence’s move to New Jersey fits a common pattern. Long Island was getting crowded, land was the currency of hope, and fertile acres in New Jersey promised room for sons and fields. Think wagons, livestock, and church records that told the story long before newspapers did.

And Hannah? Jagger families were well rooted in Southampton’s English settler circle. Her line reflects that early colonial mix of grit, Scripture, and seasonal labor. As for a link to Mick Jagger, there is no proven connection. Same surname, different continents, no documented bridge.

In the pages ahead, we will trace his births and burials, marriages and migrations. We will look at daily life, neighbors, and how a family like the Halseys fit into a colony on the cusp of revolt. If you have early Long Island or New Jersey roots, this story might feel like home.

Recompence Halsey’s Early Years in Southampton: A Glimpse into Colonial Long Island

Picture Southampton in 1700. A small English settlement on the east end of Long Island, built by families who crossed the Atlantic for conscience and land. Wooden homes lined sandy lanes, smoke from hearths curled into salt air, and Sunday set the rhythm of the week. The town’s heart beat with a Puritan pulse, strict yet steady, with church, family, and neighborly duty holding it all together.

Farms defined life. Corn, wheat, and flax filled the fields. Livestock moved with the sun, and fences mapped out inheritance as much as property. Trade came by small ships hugging the coast, carrying fish, lumber, and farm goods to nearby ports. Winters hit hard. People survived by planning, storing, repairing, and helping one another. It was not romantic. It was normal.

The wider world pressed in. British colonies spread along the seaboard, and tensions with Native communities rose and fell with land, laws, and survival. News traveled by horse and word of mouth. When wars broke out in Europe, they rippled through New England and New York, touching these quiet towns in taxes, militia musters, and fear.

Into this world came Recompence Halsey, born August 19, 1700, to Nathaniel Halsey and Anna (aka Hannah) Stansborough. He belonged to a pioneer line. His great-grandfather, Thomas Halsey, was among the original settlers who arrived in the 1640s and helped found Southampton. Thomas built one of the earliest homes in town, a place that later generations would preserve as a sign of first settlement. For more on those early roots, see the detailed account in the Thomas Halsey of Hertfordshire genealogy. If you track dates, you can also spot Recompence’s entries in the FamilySearch profile for Recompence Halsey.

The Halsey Family Roots and Recompence’s Upbringing

The Halsey story began on Long Island in 1640, when Thomas Halsey and other English families established Southampton. They brought church-centered habits, town-meeting government, and a deep regard for covenant life. Land passed from father to son, then to grandsons, along with the unwritten rules that held the place together.

Recompence grew up in that inheritance. His schooling was simple, purposeful, and close to home. He learned to read from a hornbook and the Bible, copied letters on scrap paper, and memorized passages that carried moral weight. Arithmetic meant measuring seed, tallying accounts, and making sure nothing went to waste. The catechism shaped his conscience. The Psalms shaped his speech.

Daily work trained his hands. On a typical week, he would have:

- Planted and hoed corn in straight rows, careful with seed and season.

- Tended cattle and sheep, checked fences, and hauled water.

- Cut salt hay in the meadows, stacked it tight, and sheltered it from storms.

- Helped mend tools, sharpen blades, and split shingles for roofs.

This was an apprenticeship in being useful. Skills mattered more than talk. If a neighbor needed help raising a frame for a barn, you showed up with a hammer and a strong back. If blight hit the beans, you learned to rotate fields and share seed to get through the next spring.

Community life brought him into public responsibility early. Town meetings, often held near the meetinghouse, dealt with fences, roads, commons, and disputes. Boys watched their fathers speak, then learned to listen, to vote, and to serve. Militia duty was part of that training. Recompence would have drilled with other men on open ground, musket in hand, a reminder that safety came from discipline, not luck.

Underneath it all ran a set of steady values:

- Family loyalty: kin first, and kin accountable to each other.

- Plain work: no job beneath you, no day wasted.

- Ordered freedom: rights paired with duties, voice paired with service.

- Scripture as guide: not just belief, but daily practice.

These habits formed a strong spine for a young man. By the time Recompence came of age, he knew how to read and pray, to plant and reap, to argue and to yield, to answer a call if the town needed him. That mix of skill and duty prepared him for bigger moves later in life. It made him a steady settler in a changing world, ready to claim new acres, raise a household, and carry forward the Halsey name without losing the core that built it.

Meeting Hannah Jagger: Recompence’s Wife and Her Colonial Heritage

Before we follow the wagons into New Jersey, we need to meet Hannah. She was more than a name in a church book. She was a wife, a mother, and the steady center of a home that fed, clothed, and anchored an early American family. She is also my seventh great grandmother, which makes this personal. Let’s walk through who she likely was, what she did, and why her story matters.

Hannah Jagger’s Background and Daily Life in the Colonies

Hannah came from another early Long Island line, the Jagger families known in Southampton since the 1600s. Their story fits a familiar New England arc. English settlers, some with Puritan roots, landed in New England towns like Stamford, then moved along the coast into eastern Long Island. That mix of Scripture, thrift, and landholding shaped their days and their decisions.

A likely marriage in the 1720s brought Hannah into the Halsey circle, and with it a shared life of work, worship, and kin. Families like the Jaggers and Halseys often joined by marriage to secure fields, keep property near trusted neighbors, and strengthen local bonds. You can glimpse the broad family outline on the FamilySearch profile for Recompence Halsey, which notes a marriage to Hannah and the large household that followed.

What did her youth look like? Much like Recompence’s, only with tasks that kept the entire farm economy turning. Girls learned early and learned by doing:

- Household production: spinning flax and wool, weaving linen and cloth, sewing sturdy garments for winter and work.

- Food and dairy: milking at dawn, churning butter, making cheese, drying apples and herbs, and keeping a smokehouse stocked.

- Gardening and herbs: tending kitchen plots with sage, mint, and horehound, using simple remedies for coughs, fevers, and wounds.

- Seasonal labor: candle making, soap boiling, and helping with harvests when hands were short.

Under British law, married women lived under coverture, which meant a husband controlled property and legal decisions. But do not mistake reduced legal rights for small influence. A wife’s management of stores, livestock, and textiles could tip a family from scarcity to surplus. In a cash-poor world, wool in the loft and butter in casks were as good as money.

Hannah’s world was not gentle. Epidemics like smallpox could spread quickly. Food ran tight in harsh winters, especially during war years when militia duty pulled men from fields. Women kept households steady in those gaps. They rationed flour, mended shoes, and nursed the sick with what they had on hand. That is quiet strength. Not loud, but lasting.

After marriage, Hannah stepped into the Halsey home as an economic partner. She trained children to read Scripture, to mind chores, and to carry the family’s work ethic forward. The couple raised a large family, including sons who would follow land opportunities west. Their son William Halsey is often tied to the move into New Jersey, a sign that this was a family project, not a solo experiment. The marriage itself reflected common practice in colonial towns: alliances based on trust, proximity, and survival.

If you enjoy building a profile from fragments, compare entries for Hannah on community-built sites like WikiTree’s Hannah (Jagger) Halsey page. Dates and parents can vary, so weigh sources, compare records, and keep notes on conflicts. That is how careful family history works.

Debunking the Mick Jagger Connection: Fact vs. Family Lore

Let’s get real. The last name Jagger grabs attention. People ask if Hannah links to Mick. It is a fun question, but the timelines do not line up. Mick Jagger’s ancestry traces through 19th-century England, not colonial New York or Connecticut. See the broad background on Mick Jagger and you will notice modern English roots, not a bridge to 1700s Southampton.

This is a classic genealogy trap. A shared surname invites a leap. But names repeat, branches split, and many lines never meet. It is better to follow documents, not wishful thinking.

Here is how to keep it smart and enjoyable:

- Start with what you know: parents, locations, church records, land deeds. Build out, one verified step at a time.

- Cross-check: compare multiple sources and note where data conflicts. If two dates fight, ask why.

- Use community tools: sites like familysearch.org help you compare profiles and catch mistakes.

- Stay curious, not certain: leave room for updates when new records surface.

Hannah’s real legacy is not a celebrity tie. It is the line she carried forward, including my own. It is the butter she churned, the herbs she hung to dry, the boys and girls she sent into fields and into life. It is the move to New Jersey through children like William, and the way a family’s center of gravity shifted, step by step, across colonial borders.

Family lore brings color. Good records bring truth. Keep both, but let documents lead. That is how we honor Hannah, and how we tell a story that lasts.

From Long Island to New Jersey: Recompence’s Later Life and Colonial Challenges

This is the stretch of life where routine met risk, where a farmer’s hands shaped a future bigger than his own field. Think soil, seasons, and small decisions that added up to a move across the Hudson. Recompence started in Southampton, worked land with patience, then pushed west when space and opportunity called. It was not dramatic. It was steady, and it mattered.

Daily Struggles and Opportunities as a Colonial Farmer

Picture his mornings. Oxen in the yoke, a wooden plow biting into sandy loam, wheat and corn sown with care. Sheep grazed on common fields, giving wool for winter and goods for barter. Long Island farmers raised what they ate, then traded the rest in small markets along the coast. Horses were precious, oxen were steady, and hand tools made each hour count. For a quick sense of that toolkit and crop mix, see this overview of early Long Island farming habits in How and why LI farming has changed.

Life ran on exchange, not cash. Recompence likely traded butter for nails, wool for salt, and wheat for cloth. Market days were part business, part news. Ships carried grain, lumber, and salted meat to larger ports, tying local farms to English demand and colonial supply routes. Trade with England grew in the 1700s, but price swings and import rules made planning hard. When a season failed, families leaned on stored grain, kin networks, and neighbor help.

Health was a constant worry. Smallpox visited in waves. Parents watched for fever, rash, and the long shadow of loss. Communities answered with quarantine, care, and later with inoculation where it was available. Relations with nearby Native communities rose and fell. Some exchanges were peaceful and practical, like paths, hunting rights, or repairs after storms. Others turned tense over fences, livestock, and contested ground.

What pushed a man to move? Population growth squeezed Long Island’s open land. Younger sons needed acres, not promises. New Jersey offered room for fields and family. Simple tools and local innovation made the difference: better plow shares, shared barns, and seasonal work bees that turned many hands into one strong crew. The rhythm was simple, but the vision was bold. More land meant more security for sons and daughters.

Key threads in his daily work:

- Oxen and plows: slow, reliable, and strong enough for heavy soil.

- Wheat and corn: steady staples that fed families and markets.

- Sheep and wool: clothing, barter, and winter warmth in one flock.

- Community barns: shared space for harvest, storage, and mutual aid.

The Move to Morris County and Final Years

The journey into New Jersey likely came by wagon, foot, and faith. Household goods packed tight, tools bundled, livestock pushed along slow roads. The family crossed ferries and sandy tracks, then climbed into the green hills of Morris County. Afton, now within the Morristown area, sat near fertile valleys, woodlots, and water that powered small mills. Quaker meetings left a soft imprint in parts of the county, valuing plain living, fair dealing, and peace.

Why there, and why then? His son William had a presence in Morris County, which points to family motivation. Land drew them. So did kin. The county blended agriculture with early industry. Iron forges and furnaces turned local ore into tools, nails, and cannon parts. Farmers felt that pulse in everyday ways, from buying hardware to hauling charcoal. For background on that iron backbone, see the county’s early operations in the Morris County iron industry history.

The 1770s raised the stakes. Taxes bit harder. Supply lines shifted. Frontier threats and rumors ran ahead of soldiers. Towns split into Patriot, Loyalist, and the many who tried to keep their heads down. A farmer like Recompence likely leaned Patriot or stayed practical and quiet. Fields needed tending, regardless of flags. Yet the war found its way into markets and meetings, into the cost of salt and the fate of sons.

Daily life in Morris County felt both familiar and new. Wheat still waved in summer. Sheep still dotted hills. But the sounds of hammers at forges and riders carrying war news shifted the air. If you want a period window into country life and politics in New Jersey, the narrative in The story of an old farm gives a textured, on-the-ground view.

Recompence died on May 3, 1777, at about 76 years old. That is a long life for his day. He likely rests in local ground near Afton, not far from the fields that fed his family. His years tell a simple arc, yet a strong one: from a crowded Long Island town to open New Jersey hills, from isolated settlement to colonies under strain. Quiet work built the floor under a new nation. He held up his side.

Recompence Halsey’s Enduring Legacy in American History

Some ancestors are loud in the record. Others are steady and quiet, yet their lives shape whole regions. Recompence Halsey belongs to that second kind. His story sits at the seam of two big American threads, Puritan roots on the coast and steady expansion into new fields. That is not small. That is how a country grows.

Ordinary Lives, Lasting Impact

We often credit founders and generals. But farms, family bonds, and church benches carried the daily weight. Recompence’s life models the pattern that built early America, learn the land, bind with neighbors, teach your children, then seek room to plant again. It is not flashy. It lasts.

Think about it this way. The quiet stream that feeds a river never makes headlines. Yet without it, the river shrinks. Recompence is that stream. His choices kept food on tables, hands at work, and a future open for sons and daughters. You can see the broad family arc in the community-built record at the FamilySearch profile for Recompence Halsey.

Values That Traveled: Faith, Work, and Community

What endures from a life like his? Not just land. Values moved with the wagons.

- Steady faith: worship shaped money, marriage, and work, not just Sundays.

- Work that honors the day: chores done right, tools kept sharp, fields kept in order.

- Community first: show up for a neighbor, mend a fence, serve at meeting.

These habits sound simple. They build trust. They also build resilience in hard years. When war or sickness hit, these values held families together. That is a legacy you can still feel in many towns that grew from small meetinghouses and shared fields.

Descendants Who Carried the Thread: Politics and Enterprise

Legacy shows up in what children and grandchildren do with the tools given to them. The Halsey name threads into American civic life, from local office to national work. Several Halsey descendants show up in records of public service and business leadership, including members of Congress and early industry figures. For an at-a-glance list with dates and brief notes, see this overview of Halsey descendants in public life and business.

This is the pattern you would expect from a family that prized skill and duty. Farm discipline turns into public service. Trade savvy turns into commerce. The seed was sown in a simple household, then it grew across states and sectors.

Hannah’s Hidden Power: The Maternal Engine

You cannot talk about legacy without naming Hannah. Her work made the numbers add up. She turned wool into clothes, milk into cheese, and a house into a home base that could absorb shocks. That quiet strength is often missing from the record, but it is the engine of survival.

Here is how that power looked in practice:

- Food security: stored grain, cured meat, and a steady dairy cycle.

- Skilled production: linen, candles, soap, and mended tools.

- Moral center: Scripture, songs, and rules that trained children to stand steady.

If you want to widen the lens on the family’s early foundation, the classic study of Thomas Halsey and his line offers deep context for that ethic of service and work, see Thomas Halsey of Hertfordshire.

What His Story Invites You To Do

This is where the past meets your desk. You hold a thread too. Pull it. See where it leads.

- Start with grandparents, write down names, dates, and places.

- Chase one record at a time, census, land, church, and wills.

- Compare sources, note conflicts, and keep a simple log.

- Share findings with family, bring younger voices into the hunt.

If Recompence is your seventh great grandfather, then his habits still echo in you. If he is not, the lesson still holds. Ordinary people built America with patience, grit, and care for neighbors. That inheritance is bigger than one surname. It is a way to live.

Conclusion

Recompence Halsey’s life reads like the spine of early America, steady work in a tense century, faith in community, and a move from crowded Long Island to open New Jersey for the sake of children and land. Hannah Jagger stood at the center of that story, turning raw goods into a household economy and raising a family that carried those habits forward. There is no documented tie to Mick Jagger, and that is fine, because the real heritage here is better, fields, church benches, shared labor, and bonds that held through war and winter.

If this echoes your own roots, keep going. Share a family story in the comments, compare notes with cousins, or visit the Halsey House in Southampton to stand where this began. Your turn now, gather the records, honor the names, and pass the thread to the next set of hands.